History

The history of cinema in China has often been divided into six generations, all of which involve the influence of three distinct cultural hubs; Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Mainland China. Each region has played a fundamental role in the commercial, aesthetic, and at times controversial history of cinema in China. The six generations of film making can be divided as such:

The Introduction of Cinema and the Golden Age: 1896-1940

The first Chinese feature film was released in 1905 titled, The Battle of Dingjunshan and from that moment cinema in China embarked on a tumultuous journey of censorship, creative evolution, and at various points international success. The preconceived idea of cinema in China having a unified or national message in its origin is far from the truth.

Cinema first found its footing in the 1930’s with what is referred to as the “Golden Age” of film in China. Shanghai captained the rise of film as it was the largest economic and cultural hub at the time. In an article by The British Film Institute the author Noah Cowan states that, “The 1930s in Shanghai were a golden age in many spheres of Chinese culture, cinema chief among them. Widely considered by the rest of the country as a den of iniquity, catering to foreign invaders walled off in concessions throughout the city, Shanghai presented an ‘anything goes’ attitude that proved enormously fruitful for the upstart new medium.” Even though the beginning of censorship in China by the Communist party begins at this time as well, early gems arose such as Street Angel (1937) and The Highway (1934) were still produced. These films alluded to political messages that strove for equality and questioned how film would be used as a critique to present day society. Equally as important, the rise of Ruan Lingyu, the Greta Garbo of China came to stardom and helped further the rights and equality for Chinese women in urban areas during this period of time with films such as The Goddess (1934) and New Woman (1935). However, as the medium of film was progressing so were political tensions with China’s neighboring nations.

The Second Golden Age: 1944-1951

Cinema was heavily affected by international conflict and war in the early-mid 20th century.

Cinema was heavily affected by international conflict and war in the early-mid 20th century. The first golden age of cinema ended once the Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1937 and then World War II quickly followed with a Chinese civil war, which according to British Film Institute writer Noah Cowan, “cut China in half, filled its cities with starving refugees, and resulted in the deaths of as many as 20 million Chinese.” Although this was a both physically and mentally devastating time for China, artists channeled their anguish into forms of art and film found its way back into the culture. In particular, two key films were produced after the war which are generally considered masterpieces, and one film titled Spring in a Small Town (1948) as one of the greatest films of all time.

The Communist Era: 1951-1964

During the years from 1949 to 1966, the state run industry produced a total of 603 movies and 8342 reels of documentaries. The risky and politically charged films would soon come to an end though with the beginning of a brutal crackdown on creatives known as the Cultural Revolution in 1966.

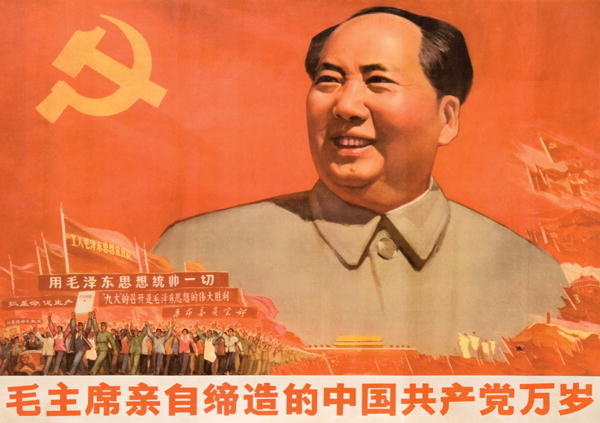

In 1949, the Communist Party led by Chairman Mao was hailed victorious over the Nationalist forces and marked the age of a new China. What followed was the execution state-sanctioned dictates of social realism on creative expression. Surprisingly, the sanctions did little to stop the most commercially successful films of the period to convey ideas in the same vein as the May 4th Movement, which was an anti-imperialist protest held by a group of Beijing students in 1919. During the years from 1949 to 1966, the state run industry produced a total of 603 movies and 8342 reels of documentaries. The risky and politically charged films would soon come to an end though with the beginning of a brutal crackdown on creatives known as the Cultural Revolution in 1966.

The Cultural Revolution and its Aftermath: 1967-1986

Leading filmmakers of the time were exiled to either produce industrial training films or sent to labor education camps. Between the period of 1966 to 1972, there wasn’t a single commercial film made in mainland China.

Nearly all of the feature films that were produced in China prior to Mao’s takeover were banned from public consumption. Under the communist’s rule during the Cultural Revolution, cinema was repurposed for “Revolutionary Model Operas” which were highly patriotic and utopic exposes of ballet, and many of these theatrical performances were adapted into films. In an NPR article by Anastasia Tsioulcas, Chariman Mao’s wife Jiang Qing spearheaded this cultural shift and promoted the operas to “”serve the interests of the workers, peasants, and soldiers and [conforming] to proletarian ideology.”

Following Chairman Mao’s death in 1976, Deng Xiaoping, one of Mao’s successors after Mao created a new economic plan referred to as the “Economic Opening”. The economic opening reflected a series of economic reforms across China including the film industry, and commercial film studios in China reopened for the first time since the beginning of the cultural revolution. That year 12 film studios would produce and distribute 46 films across the nation. Only several years later, popularity for seeing films in cinemas skyrocketed, and according to the Journal of Evolutionary Studies in Business in 1979 the annual attendance for films was 29.3 billion. One might wonder, ‘how could the attendance be so high if China’s population was only 1 billion at the time?’. This figure represents that the average citizen in China in 1979 went to the theater 29 times per year! This statistic is mesmerizing, and is most likely attributed for the new found excitement for the technology, because attendance would decline steadily year over year, until 1991 where attendance was roughly 50% lower than in 1979.

The Fifth Generation: 1986-1990

In the beginning of the early 1980’s, regional censorship on commercial films began to lessen in Mainland China as the regime’s strength grew weaker and film makers began to collaborate between Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Mainland China. The Hong Kong New Wave was a period that saw several bold young filmmakers challenge the idea of studio cinema.

Named after the French New Wave of the 1950’s and 1960’s, these filmmakers utilized “experimental techniques, personal narratives and serious artistic visions.” Some of the leaders of this generation were Ann Hui, Alan Huong, Tsui Hark, and several others all were in their 20’s and 30’s and were educated abroad. There was no specified or reoccurring plot theme among these filmmakers except that according to Culture Trip writer Sally Gao, they were “distinguished by a willingness to experiment with narrative and cinematographic techniques, as well as special effects.” Although mass entertainment and commercial films regained popularity in the mid 80’s the period of new wave cinema with films such as Dangerous Encounters of the First Kind (1980) and Father and Son (1981) exemplified that boundaries in aesthetics and visual experimentation can be taken to create a gripping film.

As authentic martial arts films began to lessen in popularity, several new forms of Chinese cinema aesthetics also came about. Jackie Chan became an international superstar and brought a new edge of humor and eye popping stunts to the silver screen that was rarely seen in former martial art films. Additionally, a new form of the genre of wuxia came about. Wuxia, which literally translates to “Martial Heroes” underwent an evolution pioneered by Hong Kong producer Tsui Hark with the lavish and challenging epic of A Chinese Ghost Story (1987), one of the first major motion pictures that fused supernatural elements with martial arts. As martial arts cinema underwent a transformation, Hong Kong and gangster crime thrillers began to take center stage in popularity as well. The pinnacle of this gangster renaissance was spearheaded by John Woo, a director, writer, and producer whose career flourished with the release of the ultra violent film A Better Tomorrow (1986). A Better Tomorrow and the core of this renaissance was regarded as nihilistic and grim, which oppose the characteristics of classic martial arts films.

From a legislative standpoint, a redefinition of the industry came in 1984 when the government stated that film was no longer an instrument to reinforce government ideologies but a healthy business opportunity. Although this sounds liberating, it also came with a pull back of funding from the government to finance films and crippled many filmmakers from telling their stories. This financial withdrawal from the government was called the “self-responsibility system”. To further these legislative developments, in 1985 the law and order of film in China was transferred to a newly created committee called the Ministry of Radio, Film, and Television (RFT). One year later, the RFT continued to create more chaos within the industry and released Policy Document 975, which effectively dismantled government regulated fixed ticket prices, and allowed studios to share box office revenue with distributors. By the end of 1986 “The organizational confusion and continuous shrinkage of the domestic film market lead to a loss of revenue of one third of all Chinese distribution companies.” However, In the book Art, Politics, and Commerce in Chinese Cinema by Stanley Rosen and Ying Zhu it was written in regards to film legislation that “In sum, film reform in the 1980’s focused mostly on the distribution-exhibition sector, granting the distributors and exhibitors a better share of the profits and more managerial autonomy. This partial reform reflected policy makers’ unwillingness to come to terms with the inefficiencies of the state-run studio system, which had long been out of touch with the market… the Chinese film industry was one of the most conservative state-run sectors in China by the end of the 1980’s.”

The Sixth Generation and New Directions: 1990-2000

Following the shocking events at Tiananmen Square in 1989, the Communist Party reaffirmed their censorship policies and authority of Chinese citizens, along with the film industry. Government funding to film productions regressed significantly which left many filmmakers to create films quickly and cheaply for several years.

This period often draws correlations to Italian Neorealism and cinema verite because of the shaky camera work, long takes, non-professional actors and actresses, and use of 16mm film. Most of these films were produced for less than $10,000 and takes an interest in hyper realistic situations such as marginalized and impoverished individuals. An example would be Zhang Yuan’s Beijing Bastards (1993) which focused on youth-punk subculture in Beijing. However, several years later there was a strong shift in the industry from a legislative standpoint where, “In 1993 the government allowed the entrance of foreign movies for the first time in Chinese theaters. Soon, these movies started outnumbering the Chinese counterparts, in both the number of films screened and ticket sales. Even if the Chinese studios were not gaining almost anything directly from the foreign films, the novelty brought more people than ever to the movies that year, even to the screenings of the local movies.” This was a sign of the beginning of the RFT adopting global business practices in the film industry, and in 1995 they further opened the Chinese market to the world by issuing a reform involving private investment. The reform ruled that any investor foreign or not “could have the right to coproduce if he were to cover 70% of the production costs.”

Things seemed to be on the up and up for the film industry in China as box office numbers rose significantly following the economic diplomacy by the RFT. However only one year later the RFT held the Changsha meeting, which resulted in a one step forward, two steps back scenario in freedom of expression and the flow of ideas. The Changsha meeting was held to cease the spread of “spiritual pollution”, which was characterized by questionable literature, pirated music, and explicit artwork. The government’s actions following the meeting in regards to film were centered around public viewings of socialist heroes and model communists. It was also decreed that 11% of screen time for a film would be given to films specially selected by the RFT to educate “children, peasants, and the army”. This led to a regression in the number of films released from 146 in 1995 to a mere 83 in 2000. In 1998, the RFT was dissolved and two new entities took over the regulation of the film industry: the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television (the SARFT) and the Ministry of Information Industry. This dawned a new era of film in China in regards to looser importations of foreign films (relative to the past) and larger budget propaganda…

The 2000’s and Beyond: A fusion of the Generations, and the coming of Hollywood in China

The days of art-house film and experiential feature films have taken the backseat to the future of film in China, as largest financial backers of films are now the new tech giants.

It is important to note that many of these generations of filmmakers and cinematic aesthetics are in a constant flux of overlap today. Although it is more structurally sound to chronologically order the realm of Chinese cinema by notable films and styles, directors, writers, and producers are inspired by previous works of art from a variety of different periods and perspectives. Presently, both a fifth and a sixth generation film can be released in the same year. In this period of artistic expression in which artists are constantly repurposing ideas and narratives of life these categories are used to describe styles rather than moments in time. Thus, in the 2000’s and beyond we see an eclectic mix of genre and styles inspired from the past.

In 2000, one of the most commercially successful and ambitious productions in cinematic history is released with Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) which grossed over $200 million dollars globally. Commercial success of Chinese films continued to grow and in 2004, China produced more than 200 movies and total industry revenue increased 66% to almost $435 million, and after an extended period of unprecedented growth in the entertainment sector for several years, over 1.6 billion tickets were sold in 2017 alone in China. That number of tickets sold equates to over $8 billion dollars. So where does this leave the state of cinema in China today?

According to economic consulting titan Deloitte, China is now entering an “unprecedented golden age”. However this is not the same type of golden age that was birthed in the early 20th century, but one that is defined as gold based on the sheer economic potential. In the same report from Deloitte it was reported that “by 2020, China’s box office is expected to reach RMB200 billion ($28 Billion) and will exceed North America as the world’s largest market in box office revenue and audience numbers.” The days of art-house film and experiential feature films have taken the backseat to the future of film in China, as largest financial backers of films are now the new tech giants. E-Commerce companies such as Alibaba and real estate developers like the Wanda Group are becoming film studios of their own, looking to merge their assets into an entertainment ecosystem that is profitable.

The realm of content in China today is focused on the blockbuster mentality, with films in 2018 such as Operation Red Sea which grossed over $579,000,000 globally. The film is a heroic and romanticized take on modern day war featuring boldness from an elite Chinese assault team that sets out to rescue Chinese citizens from crazed terrorists in Yemen. The second highest grossing film of China in 2018 was Dying to Survive which is a touching yet adventurous film about a small Chinese businessman who saves hundreds of lives when he smuggles an untested pharmaceutical drug from India to treat leukemia patients. Films such as Dying to Survive and Operation Red Sea exhibit that the Chinese movie titans are looking to broaden their audience and create a Hollywood style landscape by distributing films with the potential to gross hundreds of millions.