How to Get Your Film Into China

How are the movers and shakers in Hollywood adapting and catering to the largest international audience in the world, and what obstacles are they dealing with?

First and foremost, for an international film to be distributed in China the film must undergo a rigorous screening process by The State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film, and Television (SAPRFT) and on top of that, the committee decrees that only a certain number of international films are allowed to be distributed per year. It is widely known as a difficult process which many distribution companies seek to attain approval from. However, the Chinese government also wants it’s audience to be pleased with the stories and content they are paying for. Stanley Rosen, Political Science Professor at the University of Southern California in an interview on the subject stated, “There’s kind of contradictory impulses. On the one hand, China wants to be the best at everything. They want to succeed. On the other hand, they want to promote what the leader is promoting; Chinese propaganda or socialist core values”

Before the 1990’s, a miniscule number of American films made it overseas to Chinese audiences. China was utilizing their domestic film industry to push propaganda, however it was a failing strategy economically and culturally by the early 90’s. This can be seen through the number of ticket sales in China from this period. In 1979, 23.9 billion box office tickets were sold but by 1993, only 9.5 billion tickets were sold which equates to about an 82% dip in ticket sales comparatively. In an attempt to re-strategize, the government and studios allowed the nationwide release of The Fugitive in 1994. The film was an action packed thriller starring American archetypes Tommy Lee Jones and Harrison Ford. It was an instant hit in China. The film was so popular that according to an LA times article from the Fall of 1994 reported that scalpers outside of Chinese theaters were successfully selling Fugitive tickets for double the standard $1.25 ticket price. Following this exemplary Hollywood achievement, American studios began to lobby the U.S. government to continue to negotiate with China to allow more foreign films to be distributed. In 1994, only 10 foreign films were allowed to be distributed. Today, the quota stands at 34 foreign films entering the Chinese film market.

So what does it take for a Hollywood film to be approved by SAPPRFT and create a new revenue stream for their studio? There are primarily three strategies for something like this to occur. The three strategies are outlined below:

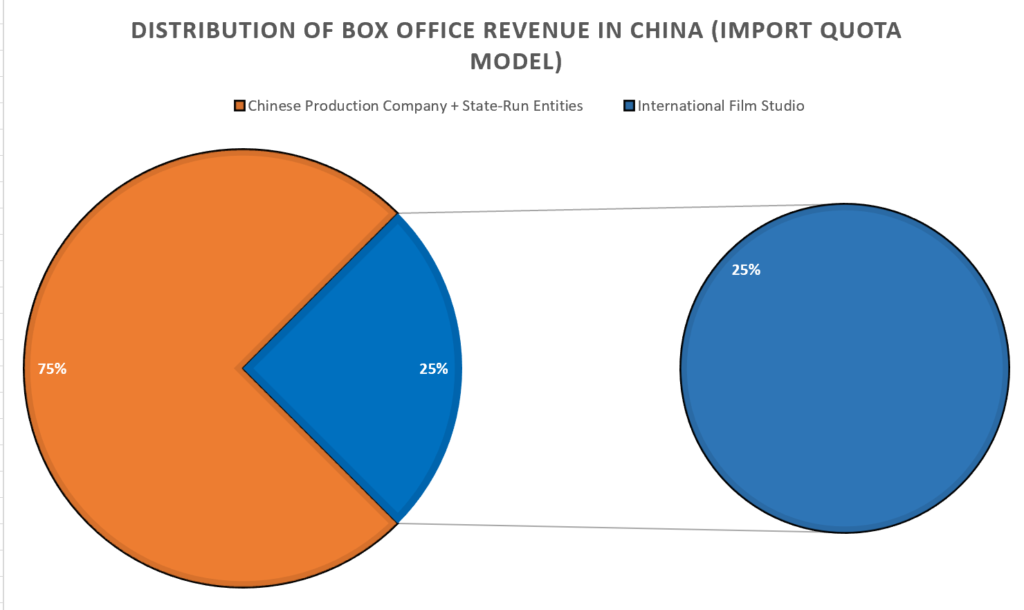

The most favorable choice for American studios of the three options is the revenue sharing model, in which the US film studio receives 25% of the revenue overseas. Say you’re the head of a big movie studio in Hollywood and you’d like your new film to enter the Chinese film market. You think it’ll perform amazingly overseas because there are giant robots fighting each other and the antagonist is an African pirate warlord (two signifiers that your film will do well in China) but 34 foreign films have already been approved for distribution in China that year. Luckily, there are two other options for getting your film into the market if your content is viable.

1. Revenue Sharing Model/Import Quota

Historically, the films that are able to be approved in this process by the SAPRFT are almost solely from the US’ big six studios: Walt Disney, Warner Bros, Paramount, Fox, Sony, and Universal.

Fenzhang pian (分账片), otherwise known as revenue sharing was introduced to the film market in 1994. The agreement allows international film studios to have their film shown in Chinese cinemas in exchange a large percentage of the revenue. Historically, the films that are able to be approved in this process by the SAPPRFT are almost solely from the US’ big six studios: Walt Disney, Warner Bros, Paramount, Fox, Sony, and Universal.

Initially when the revenue sharing model was released to the film business, China only opened its doors to 10 films per year. That quota held firm until 2002, when it was increased to 20 films. This quota increase also happened to coincide with the nation’s induction to the World Trade Organization in December of 2001. Fast forward to 2012, the quota increased to 34 films per year and has held to the present date. According to Jonathan Papish, an expert in the Chinese film industry and writer for China Film Insider, said the films imported would “basically reflect the finest global cultural achievements and represent the latest artistic and technological accomplishments in contemporary world cinema.” This is a broad statement and it is supposed to be, which gives the SAPPRFT leeway in the selection of films. Chinese representatives have also clearly stated that cultural signifiers of China’s history or it’s evolution into becoming a superpower have been heavily referenced as to what the government wants to see in a film. On the other side of the coin, Stanley Rosen at USC, a long time expert on the topic of film in China stated in an interview with Vox that, “If you look at the regulations in a very strict sense, theoretically something like a Harry Potter film should not be shown because there are elements of superstition and wizards. Things like that. But it’s very hard to deny the Chinese audience Harry Potter.” This alludes to the current manner the SAPPRFT stands on letting pure fantasy or other offences a film can garner when under review. However, if the story is a global phenomenon exceptions are sometimes made such as the Lord of the Rings trilogy. If you’d like to learn more about what the Chinese people and the government have favored in regards to content, see Government Role in Film.

In regards to the specific economics of the import quota strategy, the US Film studio receives 25% of the Chinese box office revenue and state-run film distribution companies receive a whopping 75%. Although this may seem like an eye gouging deal, keep in mind that it still remains the most lucrative of the three, and the earning potential of your film skyrockets because of sheer amount of Chinese film goers. One pertinent example would be Warcraft: The Beginning (2016) which was considered a flop in the United States. However, it still was touted as one of the most successful films of the year commercially because it grossed over $213 million in China alone.

2. Flat Fee/Buyout

It is not the most ideal strategy for getting your film in China as a studio, as there is no box office commission from the potentially hundreds of millions of dollars viewers could give you.

An alternative method for getting your film into China is called the maiduan pian (买断片) or pi pian (批片) model, otherwise known as flat fee or buy-out deal. For films that don’t make the import quota cut, studios can negotiate a deal with Chinese film distributors to receive a fixed price for granting regional film rights, but in exchange the Chinese distributor receives 100% of the revenue in the international territory. It is not the most ideal strategy for getting your film in China as a studio, as there is no box office commission from the potentially hundreds of millions of dollars viewers could give you. However on the flip side there is no need to worry about box office numbers or marketing plans. The studio takes the money and bids the distributor adieu. According to China Film Insider, the highest buyout for a film ever is $7 million for Resident Evil: The Final Chapter paid for by Leomus Pictures. It would be ideal to express the specific numbers of how many films per year enter this agreement, but it is kept confidential and Pappish reports that the “SAPPRFT is said to maintain a floating, unofficial release quota for buy-out films, so that these too, are limited in number.” Although the import quota has remained at 34 the number of international films in the Chinese market has increased beyond the quota because of deals such as the flat-fee buyout.

3. Co-Production Revenue Share Hybrid

The market is opening now, and there are many different types of deals — you can propose and discuss anything… Before, it was all flat deals, but now everyone is talking about a minimum guarantee with backend bonuses or a share of box office.

This third strategy is a hybrid of both the revenue share model and the flat fee model. This deal occurs when a local Chinese film company acquires distribution rights, and acts as a middle man or “agent” between the original rights holder and either the China Film Group or Huaxia (both state run companies). The film studio then shares the box office revenue with China Film Group or Huaxia and the Chinese distributor receives a cut of the profits as payment.

This method has emerged as the most recent and fruitful business strategy for international filmmakers to gain leverage in the increasingly attractive film market in China. Prior to this deal, the only international companies to receive a percentage of the Chinese box office were the big six Hollywood studios with the highly coveted import quota, but now with this hybrid structure the distribution of wealth has gotten slightly less concentrated and perhaps increased the size of the pie. The pie has increased because prior to the hybrid model many film studios were unwilling to entertain the idea of doing business in China. In an interview with the Hollywood Reporter Zhang Jin, CEO of Beijing film company Joy Pictures said, “The market is opening now, and there are many different types of deals — you can propose and discuss anything… Before, it was all flat deals, but now everyone is talking about a minimum guarantee with backend bonuses or a share of box office”. Zhang, who was able to import Lionsgate’s La La Land under the hybrid structure added that sellers at the Cannes Film Festival were almost universally unwilling to accept a simple flat-fee offer for China rights. Thus, the hybrid structure appears to be the most beneficial to both international filmmakers and the market in China. As a result of an increase in practical deal flow, the number of films entering China is likely to increase from more amenable revenue sharing, which in turn will give Chinese viewers more options, leading to an increase in projected box office revenue. However, it is important to note that this deal structure tends to be more fluid and is not as rigid as the other two strategies. Although it is more economically viable there are reports of additional clauses for this deal structure such as shot locations (ex: must be shot in Shanghai), to another rule stating ⅓ of the cast must be Chinese and not be portrayed as a villain.